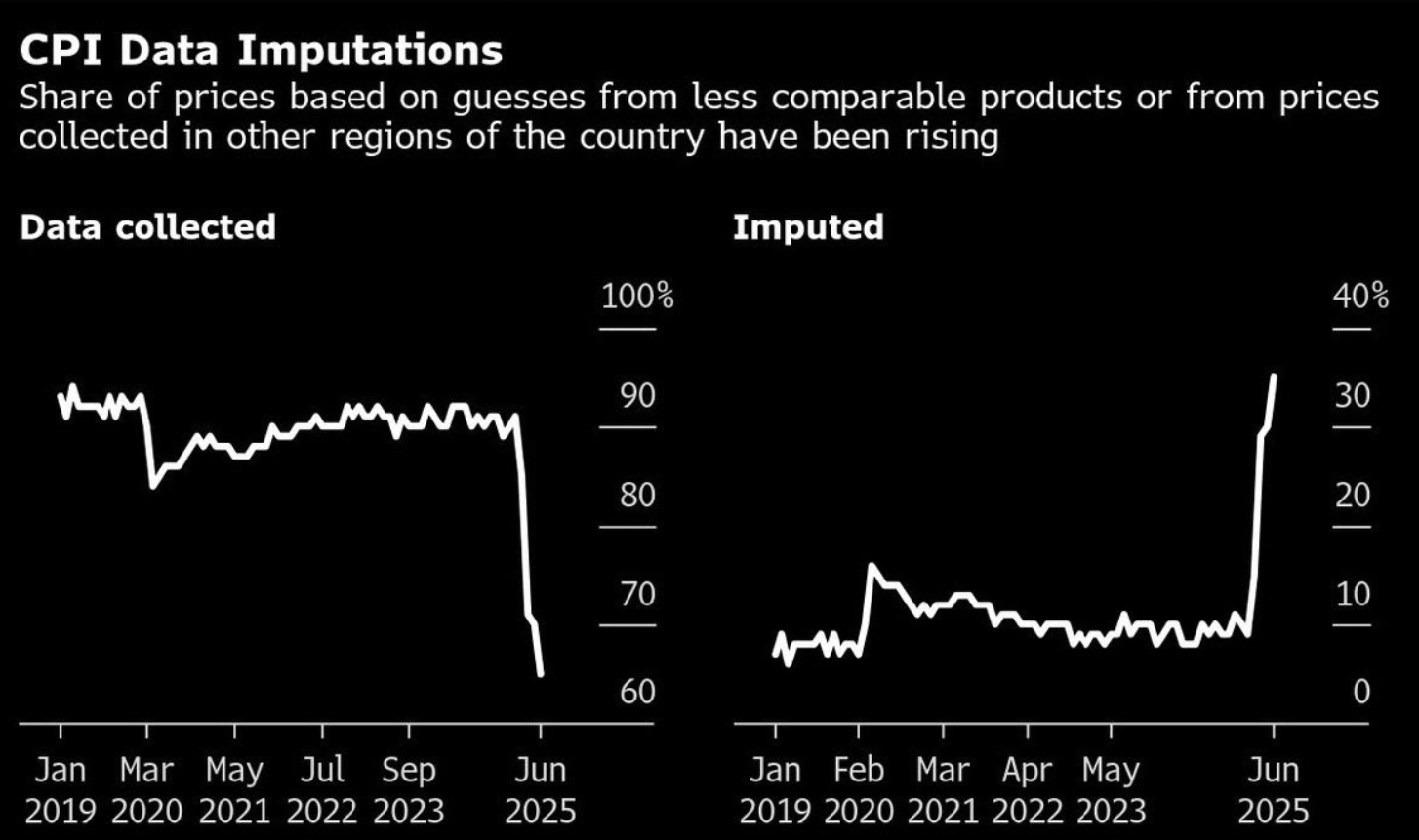

One of the biggest risks to the economy may not be the micro or macro factors themselves, but rather how those factors are currently being measured. The Consumer Price Index, the benchmark statistic that guides Federal Reserve policy, financial markets, and household expectations, is showing troubling signs of data deterioration. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the share of directly collected prices has plunged to around 60 percent, down sharply from about 95 percent just a few years ago. At the same time, the portion of prices that are imputed (estimates drawn from other goods, regions, or statistical models) has surged above 30 percent.

CPI Data Imputations from Bloomberg

Imputation has long played a supporting role in official statistics. If a store is closed or a price cannot be found, statisticians may substitute data from a comparable location. During the pandemic, when in-person data collection was impossible, imputations rose temporarily, and the expectation was that the practice would normalize. Instead, it has become entrenched at historically high levels, leaving the CPI more reliant than ever on modeled assumptions rather than observed facts.

This matters because inflation is not just a number; it is a signal that shapes the cost of borrowing, the path of wages, and the adjustment of pensions and contracts. If that data is just “guessed” then the the underlying numbers lose integrity and the risks extend well beyond spreadsheets. Policymakers may underestimate or overestimate the persistence of inflation, for example, leading the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates too high or too low for too long. Financial markets, which price trillions of dollars of assets based on expectations of inflation, are left to guess whether the official numbers truly reflect reality. Households that depend on CPI-linked adjustments to Social Security or salaries may begin to question whether the figures align with their lived experience. Once trust in statistics erodes, credibility in policy follows.

When we look at the historical backdrop, it provides a cautionary tale. In the 1970s, U.S. officials underestimated how entrenched inflation had become, leading to policy errors that fueled years of economic stagnation. In other countries, such as Argentina or Turkey, unreliable inflation statistics have often driven citizens and businesses to rely on private trackers, severing the link between official measures and everyday life. The United States is far from such extremes, but the direction of travel is concerning. For decades, the CPI has been seen as the gold standard of inflation measurement. If that reputation weakens, the fallout will be felt across the economy.

When we asked why there was a surge in imputation, we realized the answer was quite complex. First, the retail landscape has shifted dramatically toward online commerce, where prices are increasingly dynamic and difficult to capture with traditional survey methods. Budget constraints may also be a factor, as the resources required for nationwide data collection have not kept pace with the demands of a digital economy. Supply disruptions and widening regional differences in prices make consistent tracking harder. And in an ironic twist, the rise of so-called “big data” has tempted statistical agencies to rely more on modeled shortcuts, tilting the balance away from direct observation.

All of this comes at a time when the U.S. economy is already struggling to find stability. Inflation, while down from the peaks of the early 2020s, remains sticky in core areas such as housing and healthcare, which are among the hardest categories to measure accurately. Growth has slowed under the weight of three years of higher interest rates, with GDP expected to hover around one percent this year. Geopolitical tensions continue to put pressure on energy markets, driving volatility. And households, regardless of what the headline numbers say, feel squeezed by costs that seem to rise faster than their paychecks. If the official data do not reflect that experience, frustration and bad investment will mount.

The danger is that policymakers are now flying the economy with blurred instruments. In calm times, small errors in data may not matter much, but in turbulence, even minor inaccuracies can prove disastrous. Inflation measurement is too central to be left vulnerable to guesswork. Without stronger investment in data collection, more transparency about statistical methods, and a willingness by officials to acknowledge uncertainty, the economy risks drifting into a zone where policy is made on shaky ground and credibility begins to crack.

In the end, the greatest threat of 2025 may not be inflation running too hot or too cold, but the simple fact that we can no longer be sure what the temperature really is.

For investors, it’s essential to recognize that markets don’t trade on the absolute level of inflation or growth, but on the gap between what was expected and what reality delivers. If official data are distorted by heavy imputation, those expectations become less reliable, creating wider swings when reality asserts itself. A CPI release that appears benign could send yields tumbling, only for a later revision or market reappraisal to spark a sharp reversal. In this environment, volatility is less a reflection of changing fundamentals and more a symptom of unreliable measurement. The danger is that markets begin reacting not to the economy itself, but to noise in the data, amplifying uncertainty at the very moment clarity is most needed.

Note: Interlaken Advisors does not offer investment or portfolio management services.

Nothing herein is intended to be investment advice. All investments involve the risk of loss, including the loss of principal. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Interlaken Advisors editorial staff.